Posted Oct. 7, 2015

Meagan Dunphy-Daly was a 2015 John A. Knauss Fellow from North Carolina. She served as a Congressional Affairs Fellow at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Legislative and Intergovernmental Affairs, acting as a liaison between NOAA and Congress on issues of marine policy. Dunphy-Daly holds a doctoral degree from Duke University. In February 2016, Meagan was selected as a Presidential Management Fellows finalist.

This piece was been written in her personal capacity.

Seven months into my yearlong John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship — named after a founder of the National Sea Grant College Program — I began covering Arctic legislative issues for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA.

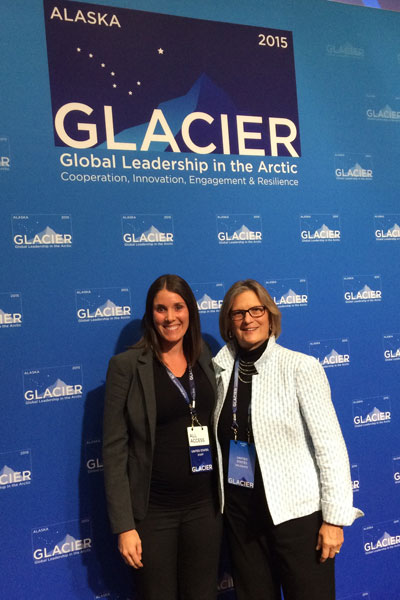

I was at the GLACIER conference to provide staff support to Dr. Kathryn Sullivan, the NOAA administrator. Photo courtesy Meagan Dunphy-Daly

I’m a warm-weather girl. Despite growing up in Michigan, where the winters often stretch into April, I have spent most of my recent history in locations that can be described as muggy, swampy and sweat inducing. Think the Bahamas, Miami and North Carolina.

And, although I did spend one chilly winter tagging humpback whales along the Western Antarctic Peninsula, I had never before studied the Arctic, much less been north of Seattle.

All of that changed this July. I work in NOAA’s Office of Intergovernmental and Legislative Affairs, and we needed someone to coordinate all of the Arctic legislative issues across NOAA. I was up for the challenge.

The Arctic is an interesting and timely place to study because it is experiencing change at rates faster than other places in the world. Large glaciers are rapidly receding, the permafrost below ground is melting, and the sea ice is disappearing.

These changes affect not only the human communities that live in the Arctic, but also the global ecosystem.

Furthermore, the Arctic acts as a refrigerator for the rest of the world. Therefore, the changes and warming in the Arctic are considered to be a preview of what the rest of the world may experience in the future.

Soon after taking on the Arctic portfolio, I traveled to Alaska and then Norway for important meetings on the future of the Arctic.

First up: Anchorage, Alaska.

As you may know, President Barack Obama also had Alaska on his list of places to visit in August. How convenient for me that we were headed to the same place for the same reason — the conference on Global Leadership in the Arctic: Cooperation, Innovation, Engagement, and Resilience, or GLACIER.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry hosted GLACIER. The event was intended to bring global leaders together to broaden awareness and heighten the urgency to address critical issues in the Arctic.

The meeting drew foreign ministers from the eight Arctic nations — Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the United States. Also present were other government officials, scientists, community members and native Alaskans, all of whom are interested in the Arctic.

My job was to advise and provide support for the NOAA Administrator, Dr. Kathryn Sullivan, who was invited to speak at GLACIER. One of the many perks of this job is that I had the opportunity to travel with Dr. Sullivan around Alaska, and witness many of the changes she would be discussing firsthand, before the conference.

My colleague, NOAA Corps Lt. Josh Slater (now Lt. Cmdr. Slater), and I also had the unique experience of spotting a stranded beluga whale and her calf. Our sighting resulted in a NOAA Fisheries stranding response using new drone technology. It was pretty cool to be able to tell Alaska’s Gov. Bill Walker how NOAA Fisheries mobilized for the stranding.

A drone captured an image of the stranded mother and calf belugas. Photo courtesy Meagan Dunphy-Daly

We also went on a glacier tour of Portage Glacier with members of the White House’s Council on Environmental Quality. On this tour, we saw that the glacier has retreated approximately three miles in the past century — including recent accelerated retreats that have been triggered by climate change.

In the past century, the Portage Glacier has retreated from where I am standing. Photo courtesy Meagan Dunphy-Daly

In addition to saving baby belugas and seeing melting glaciers, another “fringe benefit” of this fellowship is that I get a front-row seat to see our policymakers and political leaders work to influence national and international policy. After a welcoming speech by Secretary Kerry and a session with the foreign ministers on the Arctic’s unique role in influencing the global climate, Sullivan spoke about environmental intelligence.

Environmental intelligence is the timely information that is developed from reliable observations and lets us forecast future trends. Dr. Sullivan stressed the importance of community-based observations and discussed how Arctic residents have knowledge that can help provide critical environmental intelligence in a rapidly changing Arctic.

Following the session, President Obama closed out the conference by reiterating the urgent need to address the growing threat of a changing climate.

Seeing some of the changes to the Arctic first-hand during my travels really drove this message home, and supported the scientific data and policy recommendations that I had been working on in Washington, D.C., prior to my visit to Alaska.

This is the first of a two-part blog post. Read the second installment here. The shortlink for this article is http://go.ncsu.edu/o4uwjc.